Lady

Gregory – an Irish Life. Judith Hill. Sutton Publishers, Stroud,

Gloucestershire, 2005, pp 420. Photos.

Lady

Gregory – an Irish Life. Judith Hill. Sutton Publishers, Stroud,

Gloucestershire, 2005, pp 420. Photos.

This review was written on May 7th 2011

Lady

Gregory was born Isabella Augusta Persse in 1852, the ninth of the 13 children

of Dudley Persse and Frances née Barry who were part of the Anglo-Irish

aristocracy and who lived in Roxborough, an extensive estate in East Galway. Augusta

was a disappointment to her mother who had hoped for a fifth boy. It is thought

that she had little affection for the child Augusta was

more in tune with her brothers who were her nearer siblings. She was less

attached to her sisters who were conservative, straight-laced and religious.

She appears to have had a poor education and showed little interest during her

growing years in reading and other intellectual activities. She joined her brothers' outdoor

pursuits which were eschewed by her older sisters. She was considered something

of an oddity by the family.

|

A wild swan at Coole

|

After this

unpromising start, she met Sir William Gregory and

remained on friendly terms with him for a few years before accepting a proposal of marriage at the age of 25. He was a widower, 35 years older than she but this did not prevent his proposing marriage which she bravely accepted. Gregory was part of the establishment in Westminster and had been a member of parliament. He had some important diplomatic duties and appointments during his career. He was extravagant and profligate, like many of his privileged land owner colleagues, having lost most of his land in Coole close to Gort in East Galway through gambling. He was left with a mere 5,000 acres when he married Augusta.

remained on friendly terms with him for a few years before accepting a proposal of marriage at the age of 25. He was a widower, 35 years older than she but this did not prevent his proposing marriage which she bravely accepted. Gregory was part of the establishment in Westminster and had been a member of parliament. He had some important diplomatic duties and appointments during his career. He was extravagant and profligate, like many of his privileged land owner colleagues, having lost most of his land in Coole close to Gort in East Galway through gambling. He was left with a mere 5,000 acres when he married Augusta.

|

| Vanity Fair caricature of William Gregory |

During their

eleven years of marriage and after Sir William’s death Augusta Gregory showed political

instincts which were to lead her to an increasing sense of Irish nationalism,

to disapproval of the wide social, economic and cultural divisions which

existed in the country, and to the baleful effects of government by

Westminster. By the time of the Treaty ratification she had become politicised

to the extent that she had some sympathy for those who opposed the Treaty.

However, she did not approve of the military resistance to the Provisional Government

by the irregulars and she deplored the vandalism and the social and economic

consequences of the Civil War. She and Sir William were on good terms with

their tenants and, although Coole was like many other estates gradually passed

over to its tenantry, the stresses involved were alleviated by the

understanding and goodwill of both parties, and by the inevitability of land

purchase through the Land Act of 1909.

During their

eleven years of marriage and after Sir William’s death Augusta Gregory showed political

instincts which were to lead her to an increasing sense of Irish nationalism,

to disapproval of the wide social, economic and cultural divisions which

existed in the country, and to the baleful effects of government by

Westminster. By the time of the Treaty ratification she had become politicised

to the extent that she had some sympathy for those who opposed the Treaty.

However, she did not approve of the military resistance to the Provisional Government

by the irregulars and she deplored the vandalism and the social and economic

consequences of the Civil War. She and Sir William were on good terms with

their tenants and, although Coole was like many other estates gradually passed

over to its tenantry, the stresses involved were alleviated by the

understanding and goodwill of both parties, and by the inevitability of land

purchase through the Land Act of 1909. |

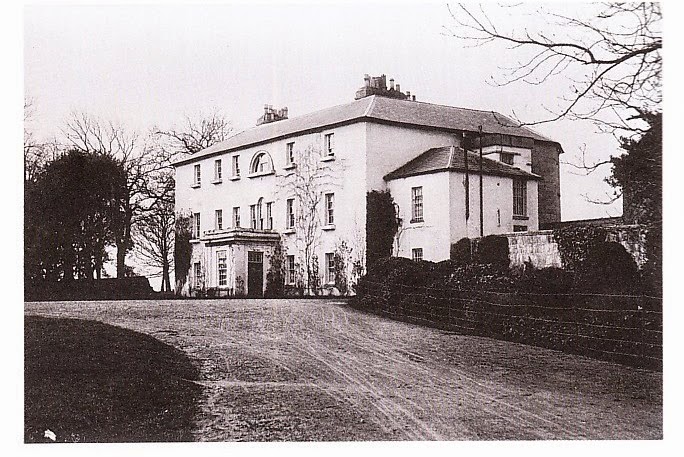

| Coole House - now demolished. |

She was quite extraordinarily prolific

with 39 plays and 18 books mentioned in the index of this biography, and with a

record of numerous essays, articles and pamphlets.

She was quite extraordinarily prolific

with 39 plays and 18 books mentioned in the index of this biography, and with a

record of numerous essays, articles and pamphlets.

While

obviously she was in a minority among the Irish landowning class and among the urban

Anglo-Irish, her career and her increasing attachment to Ireland and the Irish

social and cultural background, in contrast to the English, was part of a

movement which presaged at the turn of the century an advance of democracy and

of equality among the different Irish social classes. Such a social trend was

also driven by the advance of the land question, the emergence of a Catholic

middle class following Catholic Emancipation in 1827, the huge contribution the

Catholic teaching orders were making to secondary education among Catholics,

and by the gradual taking over of local government by the majority Catholic

population.

Reading this book left me with the thought

that 1916 may have been a great disaster with its aftermath of a destructive

War of Independence and the ‘compound disaster’ (My father’s words) of the

Civil War with its long-standing bitterness, its baleful effect on Ireland’s

reputation, its vandalism, its moral and economic ill-effects at a time of

serious post-war recession, and the futility of its genesis and its

anti-democratic origin. Unfortunately the execution of the 1916 leaders created

a martyrdom which made it difficult to make a dispassionate appraisal of the

Rising’s justification or at least to be seen to be critical of its motives. The

heroism of its leaders and the rhetoric of the Republic should not blind us to

the adverse political and military consequences of the Rising

Lady Gregory

had a strong influence on her many colleagues who joined her in literary,

cultural, academic and artistic circles. In particular she had a huge influence

on WB Yeats and his success as a poet and playwright, just as he had a powerful

influence on her. In her role in founding and safeguarding the Abbey Theatre,

she played a seminal role in management, financial and moral support, in sound

advice and in contributing plays which were widely acknowledged by national and

international audiences. Her close association with the Abbey was a constant

source of concern because of recurring personality problems, political

conflicts between nationalists and conservatives, and chronic financial

worries.

Lady Gregory

had a strong influence on her many colleagues who joined her in literary,

cultural, academic and artistic circles. In particular she had a huge influence

on WB Yeats and his success as a poet and playwright, just as he had a powerful

influence on her. In her role in founding and safeguarding the Abbey Theatre,

she played a seminal role in management, financial and moral support, in sound

advice and in contributing plays which were widely acknowledged by national and

international audiences. Her close association with the Abbey was a constant

source of concern because of recurring personality problems, political

conflicts between nationalists and conservatives, and chronic financial

worries.  |

| Yeats' signature, amongst others, on a tree at Coole Park. |

Although

separated from the masses in terms of birth, education, wealth, religion,

social life and political affiliations, she emerges from the pages of this fine

biography as patriotic, energetic and intelligent, with a great love of Ireland

and its people. She was passionate about Ireland’s folklore and its unique

Celtic culture and, above all, she played a leading role in the Celtic Revival

and in encouraging and advising those who were active during this important

phase of Irish life.

Although

separated from the masses in terms of birth, education, wealth, religion,

social life and political affiliations, she emerges from the pages of this fine

biography as patriotic, energetic and intelligent, with a great love of Ireland

and its people. She was passionate about Ireland’s folklore and its unique

Celtic culture and, above all, she played a leading role in the Celtic Revival

and in encouraging and advising those who were active during this important

phase of Irish life.

No comments:

Post a Comment